Dia Publications Spotlight: “Puerto Rican Light (Cueva Vientos)”

By Kamilah Foreman

Publications Director

On view at Dia Bridgehampton, Jill Magid’s exhibition offers an opportunity to reflect on appropriation and the creative possibilities inherent in artistic citation. Her series Homage to CMYK (2019) reconfigures images of the unlicensed prints from Josef Albers’s Homage to the Square series (1950–75) that the architect Luis Barragán used to decorate his home. Homage CMYK borrows from Albers in multiple ways. His iconic composition of concentric squares becomes the site upon which Magid layers her work. Her prints—framed silk screens on linen—cite the format and techniques of the counterfeit Albers in the Casa Barragán. Ultimately, Magid playfully literalizes Albers’s dictum that “in order to use color effectively it is necessary to recognize that color deceives continually.” In her series, color deceptions are many times refracted by the mechanical eye of the camera, the color correction of book plates, and the approximation of the halftones.

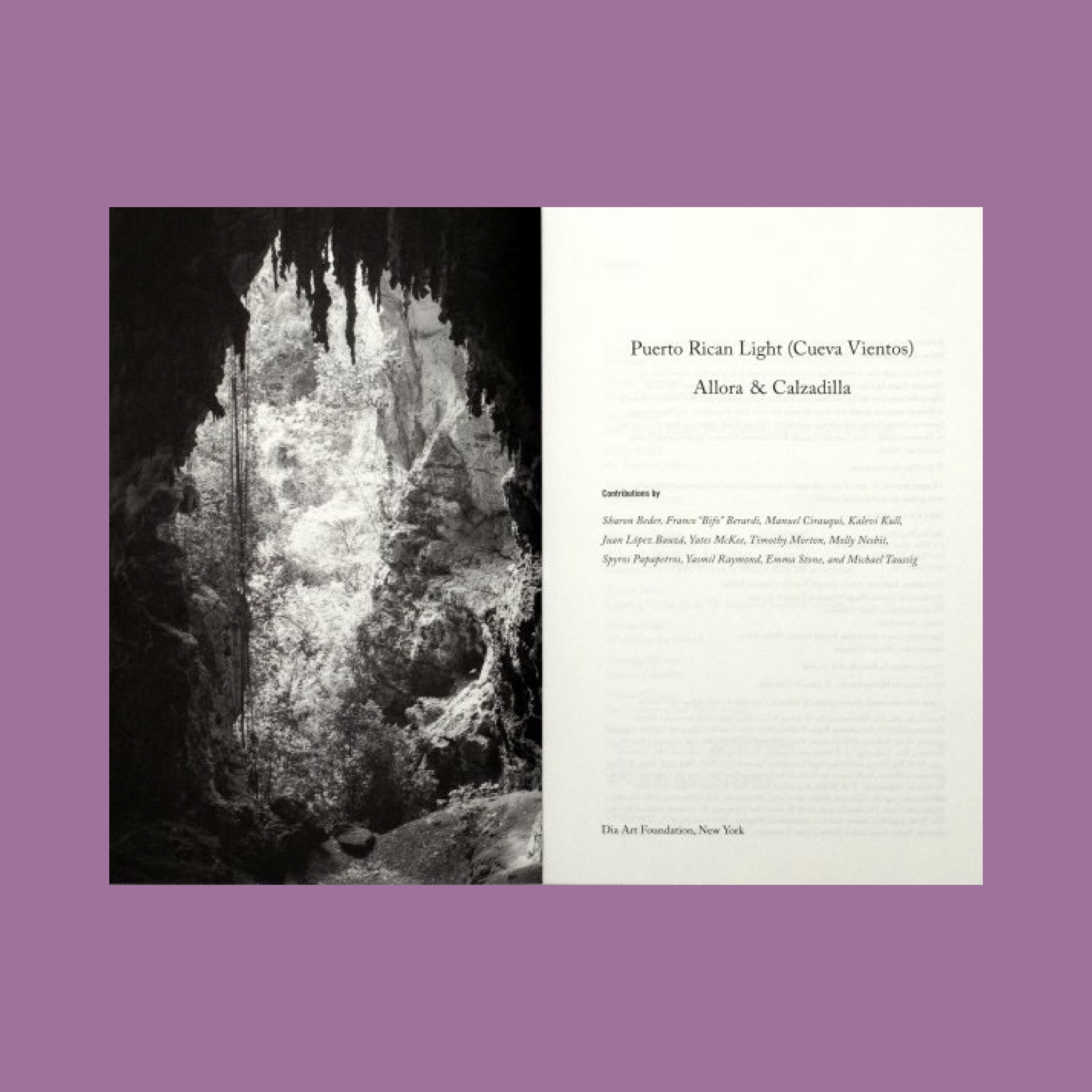

The following excerpts are from Puerto Rican Light (Cueva Vientos), a guide to Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla’s work, commissioned by Dia, which in part situates Dan Flavin’s Puerto Rican Light (to Jeanie Blake) 2 (1965) in a limestone cave system in Puerto Rico. Below, Yasmil Raymond, rector at the Städelschule, Frankfurt, and former Dia curator, offers a brief history of artistic citation to argue that the conceptual strategy not only destabilizes conventional notions of authorship and autonomy but also defies ideas of property and returns art to the cultural commons.

In the Light of Art History

Yasmil Raymond

Art is built on a condition of indebtedness. This is why, all along, artists have admitted debt to their predecessors, commemorated their admiration, or insisted on revealing how their work comes into contact with other artists. The employment of citations has been a way of thinking history and reimagining heritages as much as boundaries. I am not referring here to the use of references from popular culture but rather pastiche and montage techniques that incorporate recognizable works of art. This conceptual strategy, a twentieth-century artistic invention, brought forward generative disruptions as artists, while affirming common bonds, reshuffled systems of authorship in order to bring forward unforeseeable readings of the past. In order to qualify these agitations, art historians such as Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Douglas Crimp, Hal Foster, and Craig Owens, in the early 1980s and primarily in the United States, named this critical sensibility “appropriation art,” and in doing so reduced what initially presented a radical interrogation of authority into a depoliticized trope.

The term appropriation, no doubt, is wrapped up semantically with capitalist ideas of private property and ownership, rather than with the critique of signification that was a central concern to the artists associated with the term.[1] Originally their critique of representation was intertwined with their renunciation of the values of medium specificity and consequently with a pursuit of abolishing the notion of the originality or uniqueness in the work of art. However, the codification of references and historical frameworks also provided tools for thinking of the present and reformulating other meanings.[2] As Crimp rightly asserted in 1979, when defending their undertaking:

Those processes of quotation, excerptation, framing, and staging that constitute the strategies of the work . . . necessitate uncovering strata of representation. Needless to say, we are not in search of sources or origins, but of structures of signification: underneath each picture there is always another picture.

Furthermore, when these referencing tactics are directed to recognizable works of art, or when works of art, rather than their reproductions, are displayed as material reference, new meaning is generated.

It was this deliberate effort to reformulate the representation of meaning by diverting references from art history, advertising, and mainstream media that morphed their imaginaries along with the rapid sea changes of the 1980s. Until very recently, however, the techniques of appropriation had been understood to be an episode with unresolved paradoxes in the investigation of artistic production and systems of meaning. Foster, in his fruitful essay “The Passion of the Sign,” left it as an open-ended question when he said:

Yet a problem arose with this definition of allegorical art as well. It was too absolute to pronounce montage an “abused gadget . . . for sale,” as Buchloh did in 1981, or to dismiss appropriation as a museum category, as Douglas Crimp did in 1983. Nevertheless, when does montage recode, let alone redeem, the splintering of the commodity-sign, and when does it exacerbate it? When does appropriate double the mythical sign critically, and when does it replicate it, even reinforce it cynically? Is it ever purely the one or the other?[3]

Answering Foster’s questions remains an important task in respect to analyzing the complexity of the appropriation project and differentiating the specificities and discourses. Recent artistic production has signaled a new articulation, beyond the domain of signification of mainstream culture and pointed to the history of art as the main focal point. This impulse, not yet examined, confirms the manifestation of an appropriation technique based on temporary associations, mechanisms of loans, temporality, and situations that reconceptualize the paradigm of authorship while proposing unconditional affirmations of affiliations. . .

Now we are in a position to understand how these comparisons of forms and methods of display and their complex rejigging of forces between author and creator, borrower and debtor, all reveal an affirmation of a self-governed, autonomous production of art that is the essence of a common property. Thus arises a critique of ownership that the work of these artists is addressing in their reconsideration of art history. The work of art, in this context, is the result of a mutation layered not only by a revisionist impulse that localizes an explicit recognition but considers specific works of art to conjure up a policitized definition of authorship. Art is a non-property that belongs to all, a fortune that is a common treasure where we come together. The mutated works of art . . . reinvent the historical conception of the artist and the artists’ debts to the past. Whether inside the walls of the museum or a cave, their works articulate a decision that speaks through time, granted in each of these creations with an awareness of their codependency to history. This means that history is fierce, moving, and also generative. It is a material in itself that can be borrowed and moved to fateful ends. History is a readymade, ready to be assisted, appropriated, integrated, and mutated into situations that can illuminate with its own reflexive light where we stand.

[1] It might be said that the list of artists associated with the term “appropriation” includes names such as Dara Birnbaum, Barbara Bloom, Troy Brauntuch, Sarah Charlesworth, Jack Goldstein, Silvia Kolbowski, Barbara Kruger, Jeff Koons, Robert Longo, Richard Prince, Martha Rosler, Cindy Sherman, Philip Smith, Haim Steinbach, and Philip Taaffe, and so on. I am specifically interested in attributing the term solely for those who deployed artwork references, made their work to resemble the work of other artists, or intentionally conceived of strategies to mutate their own work with that of others—artists such as Mike Bildo, Louise Lawler, Sherrie Levine, Richard Pettibone, Sturtevant, and more recently Allora & Calzadilla, Thomas Hirschhorn, Goshka Macuga, and Rirkrit Tiravanija.

[2] Douglas Crimp, “Pictures,” October 8 (Spring 1979), p. 87.

[3] Hal Foster, “The Passion of the Sign,” The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996), p. 93.